|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HOME

CATHAR

BELIEFS

Basic

Tenets

Implications

Cathar

Believers

Cathar

Elect

Afterlife,

Heaven

& Hell

Other

Beliefs

Cathar

Ceremonies

Cathar

Prayer

The

Cathar Hierarchy

CATHAR

WARS

Albigensian Crusade

Who

led the Crusade ?

Crusader

Coats of Arms

Defender

Coats of arms

Medieval

Warfare

CATHOLIC

CHURCH

Cistercians

Dominicans

Franciscans

Cathars

on Catholics

Catholics

on Cathars

Catholic

Propaganda

"Kill

Them All ... "

Waldensians

Troubadours

CATHAR

INQUISITION

Inquisition

Inquisition

documents

CATHAR

CASTLES

Cathar

Castles

Cathar

Castle Photos

CATHAR

ORIGINS

Early

Gnostic Dualism

Manichaeans

CATHAR

LEGACY

Geopolitics

Historical

Studies

Popular

Culture

Catholic

Inheritance

Protestant

Inheritance

Cathar

Vindications

Do

Cathars still exist ?

CATHAR

TOURS

WHO's

WHO

The

Catholic Side

The

"Cathar" Side

Counts

of Toulouse

The

Cross of Toulouse

CATHAR

TIMELINE

Detailed

Chronology

MORE

INFORMATION

CATHAR

TERMINOLOGY

A

Cathar Glossary

|

Inquisition against the Cathars of the Languedoc

The Inquisition set up in the Languedoc was not the first Inquisition

set up by the Roman Church. Bishops' Inquisitions had

existed for centuries, but being local, never had the impact of

later Papal Inquisitions. The Inquisition which is the

subject of this page was the Medieval Inquisition, established informally

by Dominican

under Pope

Innocent III in the early thirteenth century and formalised

by later popes.

The more widely known Spanish

Inquisition was set up around two centuries later by their Catholic

Majesties Ferdinand (of Aragon) and Isabella (of Castile). In later

centuries another Papal

Inquisition would be created to exterminate Protestant ideas

in Southern Europe. Like the Spanish Inquisition, it would follow

the practices of the original medieval Inquisition in the Languedoc

- the one we are talking about here.

The express purpose of this original medieval Inquisition was to

discover and eliminate vestiges of Cathar

belief left in the wake of the Cathar

Crusades. During the crusades, ordinances had been

passed which imposed new penalties for heresy. After the death

of Innocent

III in 1216 Honorius sanctioned Dominic

Guzm�n's new religious order, popularly known as the Dominicans

after Dominic. The Dominicans

in turn created the first formal Inquisition. In 1233 the

next pope, Gregory IX, charged the Dominican

Inquisition with the final solution: the absolute extirpation of

the Cathars. Soon the Franciscans

would join in too, but it is Dominic

Guzm�n (St Dominic) and his followers who have left the legacy

of bitterness that endures in the Languedoc into the third millennium.

By the end of the fourteenth century Catharism had been virtually

extirpated. Before the Crusade the Languedoc, under the Counts

of Toulouse, had been the most civilised land in Europe.

People here had preferred simple asceticism to venality and corruption.

Learning had been highly valued. Literacy had been widespread,

and popular literature had developed earlier than anywhere else

in Europe. Religious

tolerance had been widely practised. Jews

enjoyed ordinary civil rights. The Languedoc had been the

home of courtly love, poetry, romance, chivalry and the troubadours.

All this was swept away by the Albigensian

Crusade and Dominic

Guzmán's Dominicans

and their Inquisition.

Procedures were developed over time, evolving from fairly amateur

attempts to establish guilt to a sophisticated mechanism that would

guarantee guilt. Initially welcomed by the Catholic community, the

Inquisition soon came to be widely hated throughout the Languedoc

by Jews, Cathars, Waldensians

and Catholics and alike - including local priests and bishops. Part

of the reason was that the Inquisition, with its papal backing,

was able to ignore the established power structure. It acted independently

of and often against the interests of local potentates, bishops,

lords and municipal councils alike. Inquisitors policed their own

activities and were answerable only the the pope himself.

Inquisitors were attacked when they appeared in public without

their armed guards. The Inquisitors' practice of digging up the

bodies of supposed heretics in cemeteries excited particular local

ire, and it was not unknown for church bells to be rung to celebrate

the murder of Inquisitors, as after the massacre at Avignonet

in 1242.

From contemporary documents we can trace the development of the

torture techniques developed by Dominican

Inquisitors. Here for example is an extract from an open letter

written around 1285 by the Consuls of Carcassonne

to Jean Galand, a Dominican

Inquisitor at Carcassonne.

Contrary the the practice and custom of your predecessors, you

have created a prison called "The Wall", which would

be better called "Hell". In it you have constructed

small cells to inflict pain and to mistreat people using various

types of torture. Some cells are so dark and airless that those

imprisoned there cannot tell whether it is night or day. They

permanently lack air and light. In other cells the miserable prisoners

remain in fetters - of either wood or metal - and are unable to

move. They excrete and urinate where they are, and cannot lie

down except on their backs on the cold earth ... In other places

in the prison they lack air and light and also food, except the

"bread of adversity, and the water of affliction" which

are provided only rarely. Some are placed on the chevelet; many

of them have lost the use of their limbs because of the severity

of the torture and are rendered entirely powerless ... Life

for them is an agony, and death a relief. Under these constraints

they affirm as true what is false, preferring to die once than

to be thus tortured multiple times ... they accuse not only

themselves but also others who are innocent, in order to escape

their suffering in any way ... those who so confess reveal afterwards

that what they have said to the Brother Inquisitors [Dominicans]

is not true, but false, and that they have confessed out of fear

of the peril of the moment. To some of those [witnesses] that

you cite you promise immunity so that they will more freely denounce

others without fear.

The original text is MS 626 BM Toulouse ff 546

v - 547v. This English translation by the webmaster. There is

a French translation in Jean-Marie Vidal, Un Inquisitor jugé

par ses victimes: Jean Galand et les Carcassonnaise, Paris,

1896, pp 39-43 and cited by Jean Duvernoy in Le Procès

de Bernard Délicieux 1319, Le Peregrinateur, Toulouse,

2001, p 8.

The bread and water quote is from the bible: Isaiah

30:20. From other sources we know that the bread was stale and

the water fetid - a diet that often resulted in death within weeks

or months.

The chevelet is an instrument of torture

These abuses and the complaints about them also occurred as Albi

and at Cordes

The procedure was that Inquisitors would announce their arrival

in a town in advance. Everyone was invited to attend and confess

their errors. When the Inquisitors arrived "volunteers"

were interviewed. If they confessed to relatively minor misdeeds,

were prepared to swear fidelity to the Catholic Church, and were

willing to provide useful information about others then they were

given a small penance and the matter was closed. Some of the consequences

of this practice were:

- It provided an opportunity for obliging Catholics to betray

friends and family, and a virtual obligation for everyone to do

so - failure to provide useful information was taken as lack of

genuine zeal and commitment to the One True Church.

- It provided a formal record of a first offence. This had a salutary

effect since a second offence carried the death penalty.

- It efficiently filtered out Cathar parfaits and other "heretics"

who were not willing to swear any oath, let alone one of fidelity

to the Catholic Church. Anyone who had not volunteered was immediately

suspected, and their failure to confess voluntarily was itself

evidence against them.

Repentant first offenders who admitted to having been Cathar heretics,

when released on licence by the Inquisition were required to:

"... Carry from now on and forever two yellow crosses on all

their clothes, except their shirts, and one arm shall be two palms

long while the other transversal arm shall be a palm and a half

long and each shall be three digits wide with one to be worn in

front on the chest and the other between the shoulders."

The dimensions are roughly 10 inches tall, 7 inches wide and

2 inches wide.

Victims were required to renew the crosses if they became torn

or destroyed by age. These yellow crosses, like the yellow badges

of a different shape that the Catholic Church required Jews to

wear, were badges of infamy - warnings to good Catholics to shun

the wearers. These crosses were known in Occitan as "las debanadoras"

- reels or winding machines. The idea seems to be that offenders

could be "reeled in" by the Inquisition at any time. This was

a serious concern since a second accusation meant a second conviction,

and a second conviction meant death.

From its beginning, the Papal Inquisition worked by ignoring

all rules of natural justice. Guilt was assumed from the

start. The accused had no right to see the evidence against

them, or their accusers. They were not always told what

the charges were against them. They had no right to legal

counsel, and if they were allowed a legal representative then

the representative risked being arrested for heresy as well. The

only sageguard was that accused persons had the right to name

their personal enemies so that the testimony of such people could

be discounted.

People

were charged on the say-so of hostile neighbours, known enemies

and professional informers who were paid on commission. False

accusations, if exposed, were excused if they were the result of

"zeal for the Faith". Guilty verdicts were assured - especially

since, in addition to their punishment, half of a guilty person's

property was seized by the Church. The Dominicans

soon hit on the idea of digging up and trying dead people, so that

they could seize property from their heirs. People

were charged on the say-so of hostile neighbours, known enemies

and professional informers who were paid on commission. False

accusations, if exposed, were excused if they were the result of

"zeal for the Faith". Guilty verdicts were assured - especially

since, in addition to their punishment, half of a guilty person's

property was seized by the Church. The Dominicans

soon hit on the idea of digging up and trying dead people, so that

they could seize property from their heirs.

Techniques of obtaining confessions included psychological methods:

threats of procedures against other family members, promises of

leniency in exchange for a confession, trick questions, sleep deprivation,

indefinite imprisonment in a cold dark cell on a diet of bread and

water. At Carcassonne,

the Inquisition walled people up. Those sentenced to the wall in

its stricter form - there were two levels - had little chance of

survival for very long. Strict immuration was in effect an alternative

form of death sentence. In the course of time the Inquisition would

develop a wide range of even more ghastly techniques to break, maim

and kill people.

Torture became a favourite method of extracting confessions for

offences both real and fabricated. Its use was explicitly

sanctioned by Pope Innocent IV in 1252 in his bull ad

extirpanda though it had been practised from the earliest

days. Inquisitors and their assistants were permitted to absolve

one another for applying torture. Instruments of torture,

like crusaders' weapons, were routinely blessed with holy water.

Torture was applied to obtain whatever confessions were required,

and sometimes just to punish people that the Church authorities

did not like - people could be and were tortured even after they

had confessed.

From time to time attempts were made to regulate procedures in

response to complaints from municipal councils. In theory, only

one session of torture was permitted, but this restraint could be

ignored - repeated torture was regarded as as the continuation of

a single session, or the rule was regarded as applying separately

to each charge, so that all the Inquisitors needed to do was generate

as many charges as they needed. Other nominal constraints on the

shedding of blood, endangering life, causing permanent disability

and torturing minors were routinely ignored - no one was in a position

to enforce them, and mutual absolution seems to have been available

on request.

Together, these techniques were responsible for the first effective

police state in Europe, where the only thoughts and actions permitted

were those approved of by the Roman Church, where no-one could be

trusted, and where duty to the totalitarian authority took precedence

over all other duties, whether those duties were to one's sovereign,

family, friends, religious beliefs or conscience.

Many of the techniques developed by the Medieval Inquisition were

picked up and used by later totalitarian regimes and police states.

Among them are the creation of racial and religious ghettos; the

forcible wearing of "badges of shame"; formalised propaganda

and forgery; spying; seizure of property, threats, false promises,

intimidation and torture; and disregard for what has long been regarded

as natural justice.

It is difficult to find any technique of modern totalitarianism

that was not pioneered by the Medieval Inquisition, right down to

the good cop / bad cop routine; physical restraint; the separation

of families; sexual humiliation; the use of agents provocateurs

and listening tubes; false promises of leniency; and softening up

new victims using psychological techniques such as leaving them

for weeks, cold and hungry, isolated in cells within hearing distance

of the torture chamber. Even water boarding was used.

Inquisitors even charged people for the equipment used to execute

members of their families - just as the very worst twenty-first

century totalitarian states do.

Jacques Fournier,

Bishop of Pamiers.

The old Episcopal Inquisition continued

in parallel with the new Papal Inquisition, so co-operative bishops

were able to work hand-in-hand with papal Inquisitors. One notable

example was Jacques

Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers.

Jacques Fournier a Cistercian

monk became Abbot of Fontfroide

Abbey. In 1317 he became Bishop of Pamiers. He undertook a rigorous

hunt for Cathar believers, which won him praise from Catholic authorities,

but alienated local people. He was an exceptional Inquisitor.

Uniquely "Monsignor Jacques" was interested in what had

really happened, not just in obtaining convictions. He kept detailed

records of his interrogations and managed to have them preserved

to provide a treasure trove for historians. He made a name for himself

by his skill as an Inquisitor during the period 1318-1325. He conducted

a campaign against the last remaining Cathar believers in the village

of Montaillou,

as well as others who questioned the Catholic faith.

He personally supervised almost all of his operations,

only occasionally using torture to extract information. The bulk

of his interrogations relied on his verbal skill at drawing out

information and encouraging people to unwittingly condemn themselves

and their friends. He conducted 578 interrogations in the 370 days

his Inquisition was in operation.

The Fournier Register is a set of records

from the Inquisition run by Jacques

Fournier between 1318 and 1325. He interrogated hundreds

of suspects and had transcripts recorded of each interrogation.

He demanded a great deal of detail from those appearing before him.

Most of those he interrogated were local peasants and the Fournier

register is one of the most detailed records of life among medieval

peasants. The records have been the focus of scholars, most notably

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie whose pioneering work of microhistory Montaillou

is based on the material in the register. Thanks to his records,

we know more about life in the tiny Pyrenean village Montaillou

than we know about life in London or Paris in the early fourteenth

century.

Prior to Bishop Jacques

Fournier the local authorities had done little to pursue

so-called heretics, and the region was one of the last areas of

Europe to be home to a significant number of adherents to the Cathar

religion, a full century after the French Crusade against the Cathars

of the Languedoc.

The severest sentence was to be burnt at the stake,

but this was rare, with this Episcopal Inquisition only sentencing

five heretics to this fate. More common was to be imprisoned for

a time or to be forced to wear a yellow cross on one's back. Other

punishment's included forced pilgrimages and confiscation of property.

Unlike the Papal Inquisitors, Jacques

Fournier was prepared to weigh the evidence objectively

and release those against whom there was no evidence of deviation

from Catholic orthodoxy.

Fournier's record was assembled in three stages:

- During the inquisition itself a scribe would

make quick notes in short form to record the conversation.

- These would then be expanded into full minutes,

which were then presented to the accused for review and alterations

in case of errors.

- Finally a final version would be recorded.

The process involved translating the dialogue

from the local Occitan

language to the Latin of the Church.

In 1326, on the successful rooting out of what

were believed to be the last Cathar adherents in the area, he was

made Bishop of Mirepoix in the Ariège. A year later, in 1327,

he was made a cardinal. He succeeded Pope John XXII (1316–34)

as Pope in 1334, being elected on the first conclave ballot. His

election as pope accounts for the fact that even a small proportion

of his records survived into modern times since they were transferred

to the Papal Archives.

Click on the following link for more on Montaillou

Click on the following link for more on Jacques

Fournier

You can also read some transcripts of Fournier's

trials, translated into English:

Bernard Delicieux

Pretty much the only Catholic churchman to have emerged from the

whole of the Cathar period with any integrity (as measured by modern

secular standards) was a Franciscan

friar called Bernard Delicieux.

Delicieux came from Montpellier, not then part of France.

He noted with some justification that there was no way of establishing

one's innocence: "... if St. Peter and St. Paul were accused

of 'adoring' heretics and were prosecuted after the fashion of

the Inquisition, there would be no defence open for them."

Delicieux was involved in the case of Castel Fabre, a unique and

revealing case in which a man was found not-guilty by the Inquisition.

It is revealing in that the only reason that a defence could be

mounted was that another arm of the Church stood to lose if a guilty

verdict were returned. The facts of the case were that the Dominicans

were trying to disinherit Castel's heirs on the grounds that he

had been a Cathar - unlikely since he had been buried in a convent.

The Franciscans

had evidence that he had left his worldly goods to them - again

suggesting that he had not been a Cathar at all. If he was guilty

then the Dominicans

would get the goods. If he were innocent the Franciscans

would get them. These unusual circumstances provided a unique opportunity

for a genuine trial based on evidence - itself an interesting fact

in that it showed that the Church new full well what a properly

conducted trial looked like.

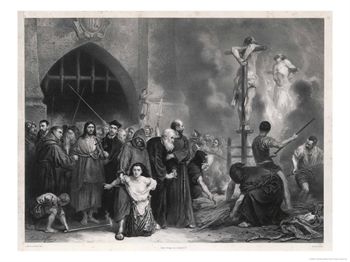

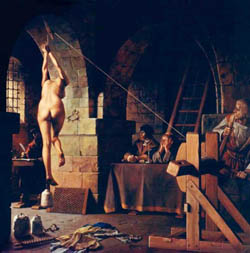

Bernard famously created such popular pressure against the Inquisition

and their hated Wall, that the king's agents were eventually obliged

to free its wretched prisoners. The scene, painted much later, by

Jean-Paul

Laurens (1838 – 1921) is depicted on the right, and may

be seen at the Musée des Beaux arts in Carcassonne

(just off the Square Gambetta).

Bernard was unpopular with the Dominican

Inquisitors whose absolute power he temporarily threatened. He was

implicated in a plot to return the Languedoc to the Aragonese rulers

in the shape of Ferrand, the King of Majorca. Jaume of Aragon, aware

of the plot, revealed it to Phlippe le Bel, King of France. The

rebels were executed and Bernard ended up incarcerated in the Wall,

sentenced to perpetual imprisonment. He was later delivered to the

Pope, Clément V , who kept him prisoner in Avignon. In 1310

he was released and went to Béziers

but a new pope John XXII had him re-arrested in 1317. Judged at

Castelnaudary

in 1319, he was "put to the question" (ie tortured). He

died in prison the following year.

Streets are named after him in Montpellier and Toulouse.

|

The "Logis de l'inquisition" -

The house of the Inquisition in Carcassonne

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921)

The Agitator of Languedoc, 1882

oil on canvas ( 115 cm c 150 cm)

Musée Des Augustins, Toulouse, France

|

|

| |

|

Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921)

La Délivrance Des emmurés de Carcassonne, 1879

oil on canvas ( 115 cm c 150 cm)

Musée Des Beaux Arts, Carcassonne, France

|

|

| |

|

Imprisoned

|

|

| |

|

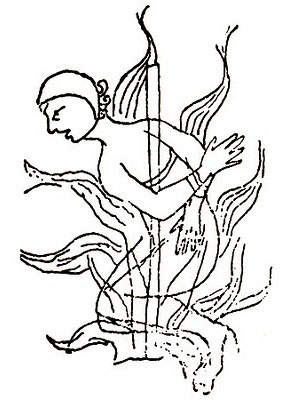

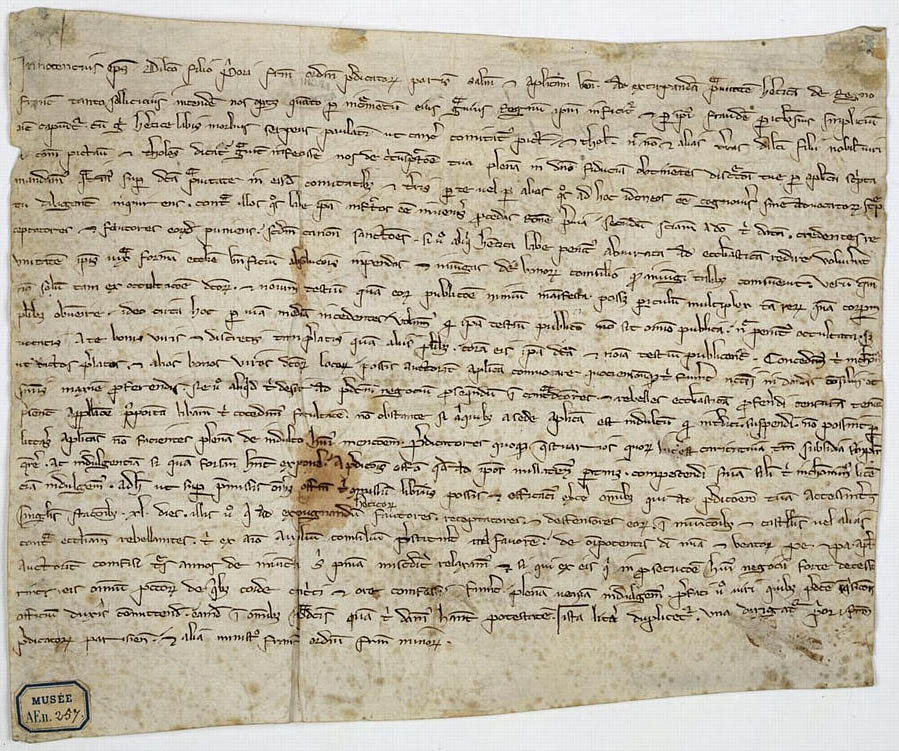

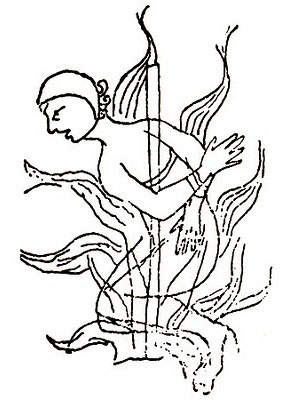

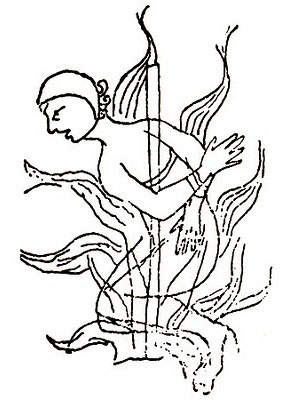

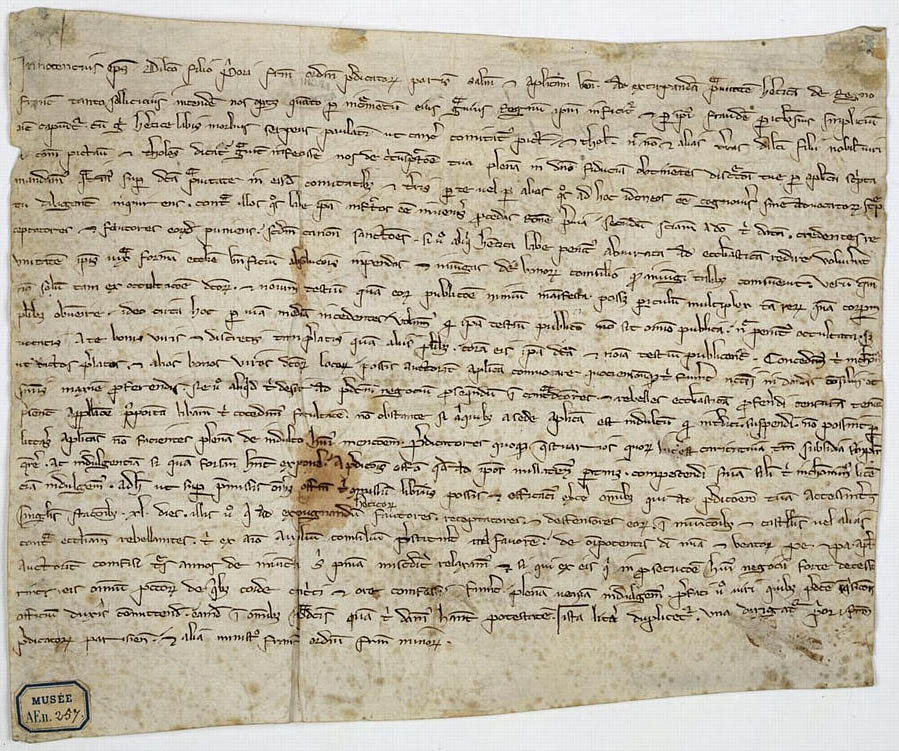

Around 12 50 Alphonse de Poitiers wrote to

Pope Innocent IV asking him to issue a bull against heresy.

This document is known in the form of a draft, on the back

of which is a sketch showing a man being burned at the stake.

|

|

This image has become famous. It is used

to illustrate many books, and on Cathar monuments, as at Les

Casses. It is a cleaned up version of the sketch on the back

of the document mentioned above.

|

|

|

The document itself (copy shown below) is

rarely mentioned, though it may have had important repercussions.

The document is undated but must have been drafted after 1249

when Alphonse took the title Count of Toulouse. Pope Innocent's

bull Ad

extirpanda, was issued on May 15, 1252, authorising

the use of torture for eliciting confessions from heretics.

Ad

extirpanda applied specifically to regions of what

is now northern Italy, but it possible that it is based on

the text of another bull, now lost, issued in response to

Alphonse's request.

|

| |

|

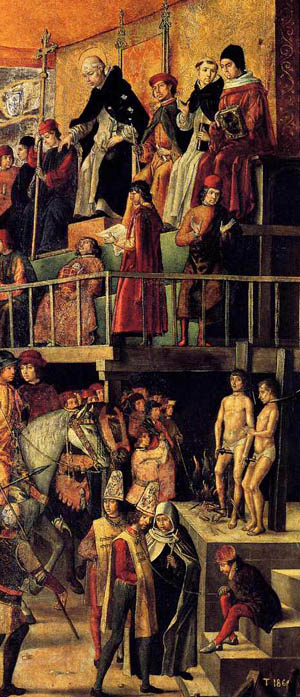

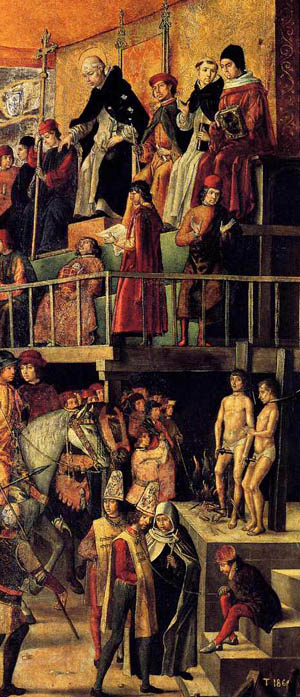

This detail of a painting commissioned by

Dominicans

shows Dominic

Guzmán judging "heretics" who are about

to be burned at the stake. For many centuries Dominicans

were proud to claim Saint Dominic as founder of the Inquisition,

but in recent years, since the Inquisition became unpopular

even in Catholic circles, a great deal of effort has gone

into trying to establish that Dominic

Guzmán had nothing to do with the Inquisition.

|

|

| |

|

Bishops supervise the burning of "heretics"

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Conrad of Marburg, detail of a 13th century

church window, Elisabethkirche Marburg

|

|

| |

Some Useful References

- Jean Louis Biget, Autour de Bernard Délicieux.

Franciscains et société en Languedoc entre

1295 et 1330, in « Mouvements Franciscains

et société française. XIIIe-XXe siècle ».

André Vauchez dir. Paris. Beauchesne, 1984.

- Jean Duvernoy (trad.), Le procès de Bernard

Délicieux – 1319, Toulouse 2001, éd.

Le Pérégrinateur

- Bernard Hauréau, Bernard Délicieux et

l'Inquisition albigeoise, 1300-1320, préface

et traduction Des pièces justificatives de Jean Duvernoy

(reprint de l'édition Hachette de 1877), Loubatières,

Toulouse, 1992. ISBN 2-86266-175-9

- M. Jouve, Vie hérétique de Bernard Délicieux,

1931

|

| |

|

Peter Martyr

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How The Inquisition developed in later Times

Back in In 1184 Pope Lucius III and the Emperor Frederick had formulated

a programme for the repression of heretics. This document, Ad

abolendum, is sometimes known as the charter of the Inquisition,

because it set the tone for future developments. The Fourth Lateran

Council in 1215 had ordered all bishops to hold an annual inquisition,

if there was a suspicion of heresy in their See. But these Episcopal

inquisitions were found to be inadequate for the task .

The Inquisition against the Cathars of the Languedoc proved a turning

point. Now the Church had a weapon that demonstrably worked. It

could be replicated and used against others. Over the centuries

to come there would be a number of Inquisitions. They have been

directed against pagans and supposed witches, dissenting sects,

Cathars, Muslims, Jews and members of other religions. They have

also been directed against freethinkers, apostates, atheists and

blasphemers.

|

|

Figure on the Basilica at Carcassonne

Heresy was often represented as a form of

wilful blindness

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Medieval Inquisition - Pope Gregory IX

A roving papal Inquisition had been set up in 1231 by Pope Gregory

IX. He extended existing legislation against heretics and introduced

the death penalty for them – indeed for anyone who dissented

from his views. Initially intended to be temporary, this Inquisition

was used to extirpate surviving Cathars in the Languedoc. Anyone

accused or ‘defamed’ was treated as guilty, and no one

once defamed got off without some punishment. After 1227 Inquisitorial

commissions were granted only to the friars, usually to the Dominicans.

The Inquisition was now the ‘Dominican

Inquisition’. Dominic

Guzmán’s threats of slavery and death for the citizens

of the Languedoc were fulfilled for a second time. First the massacres,

now the Inquisition.

The Bishop of Toulouse marked the canonisation of Dominic

Guzmán on his first Saint’s Day (4 th August 1234)

by burning a woman for her Cathar beliefs. She had confessed to

him as she lay sick in bed with a fever. She was carried to a field,

still on her sickbed, and consigned to the flames without even a

show trial.

All of the legal apparatus of the Inquisition was developed during

this period. Elsewhere, courts followed at least the basic rules

of justice: the accused knew their accusers, they were allowed legal

representation, in some places judgement was delivered by a jury

composed of peers of the accused. The old bishops’ Inquisitions

had been public hearings, but these papal inquisitions were different:

now secret hearings took place before clerical judges and prosecutors.

Guilt was assumed from the start. There were no juries, and no legal

representation for the accused. There was no habeas corpus;

no disclosure of any evidence against the accused, and no appeal.

Inquisitors were allowed to excuse each other for breaches of the

rules – which meant that in effect there were no rules. There

were secret depositions and anonymous accusations, torture and unlimited

detention in appalling conditions for those who failed to confess.

Dead people were tried along with the living. When found guilty

their children were disinherited. At least half the estate generally

went to the Church – so that the Church had a direct material

interest in a guilty verdict. Children and grandchildren of those

found guilty were all debarred from any secular office .

Gregory IX’s immediate successor died before assuming the

reins of office, but the next pope, Innocent IV, made the Inquisition

into a permanent institution. In 1252 he issued a bull Ad

extirpanda, which explicitly authorised the use of torture,

seizure of goods and execution, all on minimal evidence. Torture

was to be administered by the secular authority, but when this proved

impractical the Inquisitors were allowed to administer it themselves

(and to absolve each other for doing so). Thereafter it was an exceptional

man, woman or child who could not quickly be convinced of his or

her heresy

In theory torture could be applied only once, and could not

be such as to draw blood, to cause permanent mutilation or to kill.

Boys under the age of 14 and girls under 12 were excused. In practice

there was no one to enforce any of these safeguards, and they were

all ignored. The accused were imprisoned, often for many months,

before being examined. They were often kept in solitary confinement,

in unsanitary conditions, in a dark dungeon, and without adequate

heating, food or water. This was deliberate, and designed to ensure

that most of the accused would already have broken by the time of

the first examination. Only the strongest characters were able to

face a tribunal of hooded figures who claimed to have heard witnesses

and seen incriminating evidence. Most of the accused were prepared

to admit anything, even though they did not know what the accusations

were. Those who failed to admit their crimes were taken to the torture

chamber and shown the instruments of torture. This too was designed

to terrify and break them – the dark chamber, the horrifying

instruments, the torturer-executioner dressed and hooded in black.

If they still failed to admit their guilt they were then subjected

to torture: men, women and children alike. Some people were tortured

for years before confessing. Only the most exceptional could resist.

Every day they risked being tortured to death.

Tortures varied from time to time and place to place, but the following

represent the more popular options. Victims were stripped and bound.

The cords were tied around the body and limbs in such a way that

they could be tightened, by a windlass if necessary, until they

acted like multiple tourniquets. By attaching the cords to a pulley

the victim could be hoisted off the ground for hours, then dropped.

Whether the victim was pulled up short before the weight touched

the floor, or allowed to fall to the floor, the pain was acute.

This was the torture of the pulley, also known as squassation

and the strappado. John Howard, the prison reformer, found this

still in use in Rome in the second half of the eighteenth century.

The rack was a favourite for dislocating limbs. Again, the victim

could be flogged, bathed in scalding water with lime, and have their

eyes removed with purpose designed eye-gougers. Fingernails were

pulled out. Grésillons (thumbscrews) were applied to thumbs

and big toes until the bones were crushed. The victim was forced

to sit on a spiked iron chair that could be heated by a fire underneath

until it glowed red-hot. Branding irons and red-hot pincers were

also used. The victim’s feet could be placed in a wooden frame

called a boot. Wedges were then hammered in until the bones shattered,

and the ‘blood and marrow spouted forth in great abundance’.

Alternatively the feet could be held over an open fire, and literally

roasted until the bones fell out; or they could be placed in huge

leather boots into which boiling water was poured, or in metal boots

into which molten lead was poured. Since the holy proceedings were

conducted for the greater glory of God the instruments of torture

were sprinkled with holy water.

Whole families were accused. Family members would often be induced

to incriminate each other in order to minimise the suffering of

their loved ones. Minor heretics who confessed might escape with

light sentences, whereas denial invited trouble. The Inquisitor

Conrad of Marburg burned every victim who claimed to be innocent.

Hearings of the Inquisition denied every aspect of natural justice,

and became ever more prejudiced as time went on. They were held

in secret, generally conducted by men whose identities were concealed.

In the Papal States and elsewhere, Dominicans

acted as both judges and prosecutors. By papal command they were

forbidden to show mercy. There was no appeal. The evidence of embittered

husbands and wives, children, servants and persons heretical, excommunicated,

perjured and criminal could be used, secretly and without their

having to face the accused, their charges being communicated to

the victim only in summary form if at all.

No genuine defence could be sustained. For example, if a husband

provided an alibi, saying that his wife had been asleep in his arms

when she was alleged to have been attending a witches’ sabbat,

it would be explained to him that a demon had adopted the form of

his wife while she was away. The husband had been duped. There was

no way for him to prove otherwise. Spies were employed with the

incentive of payment by results. Perjury was pardoned if it was

the outcome of ‘zeal for the faith’ – i.e. supporting

the prosecution. Loyalties were over-ridden so that obedience to

a superior was forbidden if it hindered the inquiry, and those who

helped the Inquisitors were granted the same indulgences as pilgrims

to the Holy Land. Any advocates acting for and any witnesses giving

evidence on behalf of a suspect laid themselves open to charges

of abetting heresy. No one was ever acquitted, a released person

always being liable to re-arrest and a condemned person liable to

a revised sentence with no retrial, at the discretion of the Inquisitor.

In theory torture could be inflicted only once, but in practice

it was repeated as often as necessary on the pretext that it was

a single occurrence, with intervals between the sessions. Confessions

were virtually guaranteed unless the victim died under torture.

Then came the sentence, and execution of the sentence:

...The obdurate and relapsed were taken outside the church

and handed to the magistrates with a recommendation to mercy and

instruction that no blood be shed. The supreme hypocrisy of this

was that if the magistrate did not burn the victims on the following

day, he was himself liable to be charged with abetting heresy

(Christie-Murray, A History of Heresy, p 109) .

Almost everyone fell within their jurisdiction. People were executed

for failing to fast during Lent, for homosexuality, fornication,

explaining scientific discoveries, and even for professional acting.

In order that no blood be shed, the favoured methods of execution

did not involve the cutting of flesh. So it was that burning was

popular, the stake having been inherited from Roman law. The estates

of those found guilty were forfeit, after the deduction of expenses.

Expenses included the costs of the investigation, torture, trial,

imprisonment and execution. The accused bore it all, including wine

for the guards, meals for the judges, and travel expenses for the

torturer. Victims were even charged for the ropes to bind them and

the tar and wood to burn them. Generally, after paying these expenses,

half of the balance of the estate went to the Inquisitors and half

to the Pope, or a temporal lord. This proved such an efficient way

of raising money that it became popular to try the dead as well

as the living. Bones were dug up and burned, even after many years

in the grave. As in trials of the living, there were no acquittals,

and the heretic’s property was forfeit. In practice this meant

that the heirs of the deceased were dispossessed of their inheritances

.

|

|

|

St

Augustine of Hippo - an ex Manichaean

Sometimes called the "Father of the Inquisition"

|

|

| |

|

St

Augustine of Hippo, an ex Manichaean,

trampling other Manichaeans

underfoot

|

|

| |

|

Dominic

Guzmán(with a halo), Arnaud

Amaury, and other Cistercian

abbots crush helpless Cathars underfoot - a sanitised version

of the persecution of the Cathars

|

|

|

| |

|

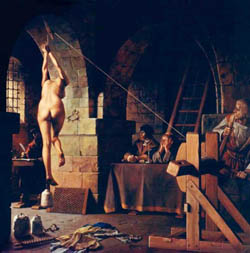

Victims were stripped and bound. Cords were

tied around the body and limbs in such a way that they could

be tightened, by a windlass if necessary, until they acted

like multiple tourniquets. By attaching the cords to a pulley

the victim could be hoisted off the ground for hours, then

dropped. Whether the victim was pulled up short before the

weight touched the floor, or allowed to fall to the floor,

the pain was acute. This was the torture of the pulley, also

known as squassation }. It was also called the strappado.

John Howard, the prison reformer, found this still in use

in Rome in the second half of the eighteenth century.

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

The Knights Templar

The trial of the Knights Templar demonstrates how unjust the Inquisition

could be. The charges of heresy against them were almost certainly

fabricated. No real evidence was ever produced to support the accusations.

The best that could be managed was hearsay evidence such as that

of a priest (William de la Forde) who had heard from another priest

(Patrick de Ripon) that a Templar had once told him, under the inviolable

seal of confession, about some rather improbable goings on.

Inquisitors obtained the most damning evidence through the use

of torture. In countries where torture was not permitted, the Templars

denied the charges, however badly they were otherwise treated and

however long they were imprisoned. As soon as torture was applied

the required confessions materialised. Inquisitors refused to attach

their seals to depositions unless they included confessions, so

that only one side of the case appeared in official records. In

France, where torture was applied freely, there were many confessions,

and also many deaths under torture. Accused persons who retracted

their confessions faced death at the stake as relapsed heretics

.

|

Quote from J. Michelet (ed.), Patrologiae

Cursus Completus, Series Latinae, 221 vols. (Paris,

1844-64), vol. 1, PP 31-32; translated by Barber, The

Trial of the Templars, p 124.

|

|

Under torture, the Templar Grand Master himself, Jacques

de Molay, confessed – though it is likely that his

confession was fabricated or at least added to, since he

was dumbfounded when it was read out to him in public. When

he tried to mount a defence on behalf of the Templar Order,

he was told that "in cases of heresy and the faith

it was necessary to proceed simply, summarily, and without

the noise of advocates and the form of judges". Since

all of the Order’s assets had been seized there was

in any case no way for him to mount an effective defence.

Even by asking to do so he invited death at the stake, as

a number of churchmen pointed out at the time.

|

When no English Templars could be induced to confess, the Pope

insisted that torture be applied. He was shocked to discover that

the common Law of England prohibited torture and insisted that his

law "God's Law" be applied and torture inflicted. When

the Archbishop of Mainz delivered a verdict favourable to the Templars

at a provincial council, the Pope simply annulled it. When it looked

as though the Templars in Cyprus might be acquitted, the Pope ordered

a new trial backed by torture. When the fate of the Templars was

considered at the Council of Vienne late in 1311 the cardinals had

‘a long dispute’ as to whether a defence should be heard

at all. In the event no defence was heard and the Pope enforced

the King of France’s demand that the Order be suppressed.

|

Templar assets were divided up between Church and State,

and interest in the fates of individual Templars immediately

subsided. Jacques de Molay retracted his confession knowing

what the consequences would be, and was roasted alive, slowly,

over a smokeless fire on 18 th March 1314. A document recently

re-discovered (The Chinon Parchment) reveals that the Pope

knew the Templars to be innocent of the charges against them.

|

|

|

The Chinon Parchment was published by

Étienne Baluze during the 1600s, in Vitae Paparum

Avenionensis ("Lives of the Popes of Avignon").

Dr Barbara Frale discovered that in it Pope Clement

V secretly absolved the last Grand Master Jacques de

Molay, and the rest of leadership of the Knights Templars,

in 1308, from charges brought against them by the Medieval

Inquisition. The parchment is dated Chinon, 1308 August

17th - 20th. The Vatican keeps an authentic copy with

reference number Archivum Arcis Armarium D 218, the

original having the number D 217.

|

|

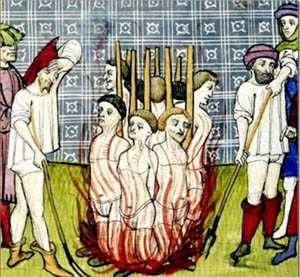

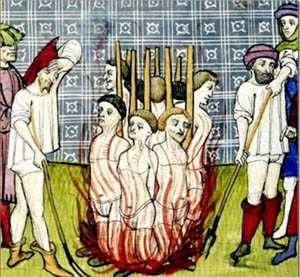

The activities of the Medieval Inquisition were so terrible that

the memory of them has survived throughout Europe to the present

day. Some Christians acknowledge that this body was one of the most

sinister that the world has ever known, and now attribute its work

to satanic forces.

|

Knights Templars being burned alive

Illustration, anonymous Chronicle, From the Creation of

the World until 1384. Bibliothèque Municipale,

Besançon, France.

|

|

| |

|

|

Detail of a miniature of the burning

of Jacques de Molay (the Grand Master of the Templars) and

Geoffroi de Charney.

From the Chroniques de France ou de St Denis, BL Royal MS

20 C vii f. 48r

(In fact they were roasted slowly, rather than burned like

this)

|

|

| |

| |

|

In 1310, 54 Templars were burned outside

Paris.

Manuscript Image from J. Riley-Smith (ed.), The Oxford

Illustrated History of The Crusades

(Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2001), p.244

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The Spanish Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition was established in Barcelona in 1233.

Five years later its authority was extended to Castile, Leon and

Navarre. This was essentially an extension of the Inquisition established

to extirpate the remnants of Catharism. Over 200 years later another

inquisition was to appear : the Spanish Inquisition. Their

Roman Catholic Majesties, Ferdinand and Isabella, established it

in 1479, with the explicit sanction of Pope Sixtus IV, who in 1483

also confirmed the Dominican

friar Thomas de Torquemada as Grand Inquisitor for Aragon and Castile.

The Inquisition was initially directed against Jewish and Muslim

converts who were suspected of returning to their own religion,

and thus being guilty of apostasy. (Many had converted to Christianity

only under threat of death.)

The process was much the same as that of the Medieval Inquisition,

and indeed was deliberately modelled on it. It too was manned mainly

by Dominicans.

They copied the methods of arrest, trial, punishment, staffing,

and procedure, even down to the blessing of the instruments of torture.

There were a few differences from the Medieval Inquisition, for

example there were cases where people were able to mount a defence

and were acquitted. Better records were kept. Some Inquisitors seem

to have been relatively enlightened and were suspicious of accusations

motivated by the self-interest of accusers. Prisons seem to have

been better than most ecclesiastical prisons – there are cases

of people committing minor heresies in order to get themselves transferred

from ecclesiastical prisons to those of the Inquisition. On the

other hand, this may say more about ecclesiastical prisons than

Inquisition prisons, for even in the latter many died before their

cases were heard. In the early days the accused were able to appoint

their own defence counsel, but by the mid-sixteenth century this

had changed. If advocates were permitted they had to be abogados

de los presos, officials of the Inquisition, dependent upon

the Inquisitors for their jobs. It is fair to assume, as their clients

did, that these court officials were aware of their employers’

expectations and of the dangers of doing their jobs too well .

|

It was widely accepted that the Inquisition existed only

to rob people, as they openly affirmed (Kamen, The Spanish

Inquisition, p 150). Both rich and poor knew that it

was the rich who were most at risk. The fact that the Inquisition

funded itself from the property it confiscated meant that

in effect it burned people on commission. Individual Inquisitors

also funded themselves, acquiring great wealth during their

careers. Some Inquisitors were known to have fabricated evidence

in order to extort money from their victims, but even when

discovered they received no punishment. Similarly their staff

of helpers, called familiars, were free to commit

crimes without fear of punishment by the secular courts. After

1518 this was formalised. Familiars enjoyed immunity from

prosecution similar to benefit of clergy or modern diplomatic

immunity. This provided another cause of popular scandal,

along with their exemption from taxation .

|

|

|

"Some Inquisitors. ..": A good

example is the Inquisitor Diego Rodriguez Lucero, who

fabricated evidence, extorted a fortune and killed hundreds

to conceal his crimes. He might well have continued

his career indefinitely had he not overstepped the mark

by arresting the Archbishop of Granada and torturing

his relatives to obtain evidence against him. See Kamen,

The Spanish Inquisition, PP 75-7

|

|

The activities of the Inquisitors were resented by all sections

of society, and the papacy was obliged to interfere from time to

time, although the Inquisitors were powerful enough to ignore it

on many occasions. Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull on 18 th April 1482

protesting that

in Aragon, Valencia, Mallorca and Catalonia the Inquisition has

for some time been moved not by zeal for the faith and the salvation

of souls, but by lust for wealth, and that many true and faithful

Christians, on the testimony of enemies, rivals, slaves and other

lower and even less proper persons, have without any legitimate

proof been thrust into secular prisons, tortured and condemned as

relapsed heretics, deprived of their goods and property and handed

over to the secular arm to be executed, to the peril of souls, setting

a pernicious example, and causing disgust to many.

When someone was arrested all of his or her property was seized.

This was then sold off as required to pay for the upkeep of the

person arrested. This might go on for years until the property was

all sold off. The families of the accused were not supported, so

they also suffered hardships. In some cases the children of rich

parents starved in the streets. Others survived by begging. The

King, Ferdinand, intervened from time to time, and later, in 1561,

provision was made to support dependents– although the effect

was to use up the sequestered assets that much faster.

The accused were invited to confess their crimes but not told what

these crimes were. Sometimes it was difficult to guess, as any of

the following were considered serious crimes: changing bedding on

a Friday, not eating pork, dressing in certain ways, wearing earrings,

speaking in foreign languages, owning foreign books, casual swearing,

criticising a priest, or failing to show due reverence to the Inquisition.

Three methods of torture were popular, the garrucha, the

toca and the potro. The garrucha was

the strappado under another name. The toca was a water

torture - copied by Us forces in the early twenty-first century.

A linen strip was forced down the throat of the accused and water

poured down it until the stomach was distended. The potro

was a form of rack combined with tourniquets.

Surviving records of these torture sessions make harrowing reading.

As the torture progressed the victims were soon ready to admit to

anything. They would admit to having done whatever they were accused

of. But since they did not know the specifics of the accusation

they could not admit to them item by item. More torture was applied.

They admitted to whatever their accusers had said, but again they

could not be specific because they did not know what their accusers

had said. More torture was applied. They begged for clues. They

begged for mercy. They were told to confess. They confessed to crimes,

real or invented, apparently whatever they could think of. They

asked what it was the Inquisitors wanted and offered to confess

to it whatever it was – still not good enough. More torture

was applied. And so it went on, sometimes until they went mad. Sometimes

they died under tortured. Many died in prison. Others committed

suicide. Of the survivors some were disabled for life.

The lucky ones got off with penance, whipping or banishment. Others

were condemned to slow deaths in prison or in the galleys. As the

writer George Wryly Scott noted in his book A History of Torture:

Of all the punishments which the Inquisition inflicted in the

name of God, for sheer long-continued cruelty, nothing ever rivalled

the treatment of the galley-slaves, who were flogged very nearly

every day during the period they laboured at the oars…It

was a fate worse than death. For, as everyone knew, it meant a

life of the most terrible hardship man could possibly endure and

yet continue to live; it almost inevitably entailed death long

before the sentence was completed. It meant, in the majority of

instances, that the victim was gradually whipped to death.

Others were condemned to public execution, but this was rarely

a simple matter of dispatching the victim. Even those who confessed

immediately were tortured. Execution was not the sentence

– it was an additional sentence. At the end of the

trial a public ceremony was held called an Auto-da-fé

(Portuguese for Act of Faith). The victim was dressed in

a penitential tunic ( san benito) painted with a design.

Impenitents wore tunics painted with pictures of their wearers burning

in Hell with devils fanning the flames. On their heads they wore

3-foot-long pointed pasteboard caps (corozas), also painted.

Around their necks they wore nooses, and in their hands they carried

candles. Anyone judged likely to speak out against the Inquisition

was gagged. After a procession came a Mass and sermon, in which

the Inquisition was praised and heresy condemned. The sentences

were read aloud and then carried out. As usual the secular authorities

were obliged to burn victims on the Church’s behalf on the

grounds that ecclesia non novit sanguinem – the Church

does not shed blood. Burning generally took place on Sundays or

festivals in order to attract the largest possible audience. Participation

was a meritorious act – so for example any persons who helped

collect firewood would earn a remission of their sins.

A slow roasting was considered preferable to quick incineration.

Victims were tied high up on their stakes, partly to give the crowds

of faithful a good view, partly to prolong the agony. Sometimes

there was further torture before the fire was lit. For example Protestants

who refused to recant had burning sprigs of gorse thrust into their

faces until they were burned black. The whole event was a popular

festival for the devout, who enjoyed the spectacle and ridiculed

the victims in their death agonies. The events were closely linked

to royal spectacles. The king was obliged by his coronation oath

to attend these mass burnings. Such burnings were even held to help

celebrate royal marriages .

Children and grandchildren of the condemned were prohibited from

becoming priests, judges or magistrates, lawyers, notaries, accountants,

physicians, surgeons, or even shopkeepers. They could not become

mayors or hold other public offices. Some penalties passed from

generation to generation without limit. Under statutes of limpieza

de sangre, the descendants of heretics, like those of Jews

and Moors, suffered civil disabilities because of their ‘tainted

blood’. San benitos worn by heretics were hung up

in local churches as an eternal badge of shame so that no one should

forget their heretical ancestors.

The Spanish Inquisition continued its work for centuries, and exported

its practices to the New World. The Portuguese exported similar

practices to their colonies, not only to the New World but also

east to countries like Goa. The fact that few of the indigenous

people of the New World could be induced to convert should have

meant that there was little recidivism, and therefore little heresy.

In fact many hundreds of heresy trials were conducted in South America

.

|

A procession by the inquisition in Goa -

Dominicans in the lead, victims in sanbenitos behind. From

Picart's 'The Ceremonies and Religious Customs of the Idolatrous

Nations' (English version, London, 1733-38)

|

|

The Spanish Inquisition continued to execute its victims into the

nineteenth century. When the French army invaded Spain in 1808 the

Dominicans

in Madrid denied that they had torture chambers in their building.

The soldiers searched and found that they did. The chambers were

full of naked prisoners, many of them insane. Similar discoveries

were made throughout the country.

While it existed, the Spanish Inquisition was regarded with horror,

even by Roman Catholics from other countries who witnessed its activities.

It was abolished by Joseph Bonaparte in 1808, but it was reintroduced

by Ferdinand VII in 1814, and finally ended by government decree

on 15 th July 1834 .

|

|

|

|

The Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, more correctly the Congregation of the

Inquisition, was set up in 1542 by Pope Paul III to help eradicate

Protestantism from Italy. It was composed of cardinals, one of whom

had proposed its establishment in the first place. He later became

Pope himself, taking the name Paul IV. A keen opponent of the free

exchange of ideas, he enjoys the distinction of having put even

his own writings on the Index.

Procedures of the Roman Inquisition were no more just than those

of earlier inquisitions, and executions became more common than

in Spain. Freethinkers and scientists were added to the existing

categories of victim for torture and execution. It was this inquisition

that was responsible for burning the foremost philosopher of the

Italian Renaissance, Giordano Bruno, in 1600; and for inducing the

foremost scientist, Galileo, to recant under the threat of torture

.

Book burning was as popular as elsewhere, but political repression

added a new dimension. This persecution too continued for centuries,

until the papacy became too far out of step with the rest of Western

Christendom. Eventually the Church decided to change its ways, or

at least give the appearance of changing them. Pope Pius VII purported

to forbid the use of torture in 1816, although in practice it continued

to be used for decades to come. Public burnings became something

of an embarrassment too. The answer was not to abandon executions

but to carry them out more discreetly. Pius IX, in an edict of 1856,

sanctioned ‘secret execution’. In the Papal States things

had changed little since the Middle Ages – it was for example

still a crime to eat meat on a feast day. Political trials were

conducted by priests, whose power was absolute. Again, the accused

were not permitted legal representation, nor were they allowed to

face their accusers. All this came to an end only in 1870, when

the Papal States were seized. The last prisoners of the Inquisition

were released , and the Pope became a self-confined prisoner in

his own palace.

In 1908 the Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Inquisition changed

its name to the Holy Office. In 1967 it changed it again,

this time to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

It still functions from a large building near the sacristy of St

Peter’s in Rome. Since 1870 its dungeons have been converted

into offices. Despite the name change, there is no apparent embarrassment

about its history. On the contrary it still conducts heresy trials

according to rules that breach what are elsewhere regarded as elementary

rules of natural justice .

Despite the methodical destruction of Church torture chambers in

modern times there is still evidence of their existence –

not only medieval records but the testimony of early penal reformers

like John Howard (1726–1790). Museums throughout Europe display

instruments of torture carefully designed to inflict the maximum

of pain over prolonged periods without shedding blood (a Papal requirement).

Because so many records have been lost, no one knows how many men,

women and children were tortured or burned to death over the centuries

by the various inquisitions. Similarly undetermined is the number

of families dispossessed, children orphaned, communities destroyed.

All we can say with certainty is that the pain and suffering that

was caused is incalculable. Even sources sympathetic to the Roman

Church have accepted estimates in excess of nine million.

One irony is that the Medieval, Spanish and Roman Inquisitions

would all have burned Jesus as a persistent heretic if he had appeared

before them. They might each have done so on different grounds:

for example for advocating absolute poverty, for practising Judaism,

and for criticising St Peter.

|

|

Execution of Mariana de Carabajal at Mexico.

Illustration from El Libro Rojo, 1870.

Ten members of Mariana de Carabajal's family were tried for

practicing Judaism, and burned at the stake. Mariana (who

lost her reason) was tried and put to death at an auto-da-fé

held in Mexico City on March 25, 1601

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

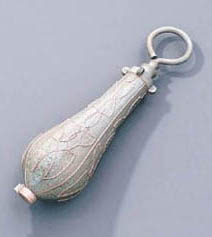

The Inquisition worked by ignoring all rules of natural justice.

Guilt was assumed from the start. The accused had no right

to see the evidence against them, or their accusers. They

were not even told what the charges were against them. They

had no right to legal counsel, and if exceptionally they were allowed

a legal representative then the representative risked being arrested

for heresy as well.

People were charged on the say-so of hostile neighbours, known

enemies and professional informers who were paid on commission.

False accusations, if exposed, were excused if they were the result

of "zeal for the Faith". Guilty verdicts were assured - especially

since, in addition to their punishment, half of a guilty person's

property was seized by the Church. (Dominicans

soon hit on the idea of digging up and trying dead people, so that

they could retrospectively seize their property).

Techniques of obtaining confessions included threats of procedures

against other family members, promises of leniency in exchange for

a confession, trick questions, sleep deprivation, indefinite imprisonment

in a cold dark cell on a diet of bread and water, and of course

a wide range of even more ghastly techniques. Torture was

a favourite method of extracting confessions for offences both real

and fabricated. Its use was explicitly sanctioned by Pope

Innocent IV in 1252 in his bull ad extirpanda. Inquisitors

and their assistants were permitted to absolve one another for applying

torture. Instruments of torture, like crusaders' weapons,

were routinely blessed with holy water.

Torture was applied liberally to obtain whatever confessions were

required, and sometimes just to punish people that the Church authorities

did not like. Together, these techniques were responsible

for the first police state in Europe, where the only thoughts and

actions permitted were those approved of by the Roman Church, where

no-one could be trusted, and where duty to the totalitarian authority

took precedence over all other duties, whether those duties were

to one's chosen sovereign, family, friends, beliefs, conscience,

or even to the truth.

|

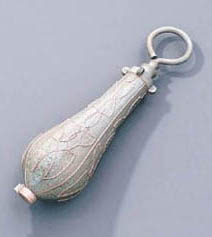

A Pear of Anguish, or "Pope's Pear"

- Closed and open

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bernard Délicieux and Jean-Paul Laurens

Bernard Délicieux, a Franciscan friar who stood up against

the excesses of Dominican Inquisitors in the 1300s.

| |

| |

|

Jean-Paul Laurens, Freeing of the Imprisoned

of Carcassone, 1879.

La délivrance des emmurés de

Carcassonne. Jean-Paul Laurens, 1879, Oil on canvas, 14 feet

1 inch x 11 feet 5 inches. Musée Des Beaux-Arts, Carcassone,

France.

|

|

|

| |

|

Jean-Paul Laurens, The Agitator of Languedoc,

1887. Oil on canvas, 45 1/4 x 59. Musée Des Augustins,

Toulouse.

The Agitator of Languedoc depicts

Bernard Délicieux facing his judges.

|

|

| |

|

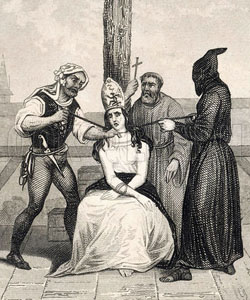

Jean-Paul Laurens, L'Interrogatoire, 1881

Dominican Inquisitors prepare to torture

Bernard Délicieux using the strappado

When the winch is turned Délicieux will be hoisted

off the floor by his hands which have been tied behind his

back. If this is not sufficient then he will be allowed to

drop then pulled up quickly, dislocating his shoulders. If

that does not work, ever heavier weights will be attached

to his feet and the process repeated until the required result

is obtained.

|

|

| |

|

Jean-Paul Laurens, After the Interrogation,

1882. Oil on canvas, 32 1/8 x 48. Private collection.

This is from another sequence by Jean-Paul Laurens (so the

victim is not Bernard Délicieux )

|

|

| |

|

Jean-Paul Laurens, Le pape et l'inquisiteur,

1882. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 52 7/8. Musée Des Beaux-arts,

Bordeaux.

The Pope and the Inquisitor shows Pope Sixtus

IV with Torquemada, who is examining the Papal Bull making

him Inquisitor General of Castilla and Aragon in 1483.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Jean-Paul Laurens, The Walls of the Holy

Office (1883) depicting the role of the Pope’s hidden

adviser;

Jean-Paul Laurens, The Great Inquisitor in

the Time of the Catholic Kings (1886) depicting the decision

to persecute Jews in the Spanish kingdom

|

| |

|

Jean-Paul Laurens, The Men of Holy Office,

1889. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 79 1/2. Musée de Beaujeau,

Moulins.

Showing the effectiveness of repression in

the Roman Catholic Church-State in this portrayal of Inquisitors

examining the files of those whose lives are in the balance

(These are Dominicans in their summer outfits)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Catholic & Inquisition Documents

Including Inquisition Depositions

Canon

Four of the Council of Tours (1163)

Canon

Three of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215)

An

Extract from the Chronicle of Ralph, abbot of Coggershall concerning

the discovery of a Cathar in Rheims

Bernard

Gui,

Extract from the Inquisitors' Manual [1307-1323], Practica inquisitionis

heretice pravitatis on the Waldensians

Bernard

GUI,

Extract from the Inquisitors' Manual [1307-1323], Practica inquisitionis

heretice pravitatis on the Beguines

Bernard

GUI,

Extract from the Inquisitors' Manual [1307-1323], Practica inquisitionis

heretice pravitatis on the Albigensians (Cathars)

Caesarius of

Heisterbach: Medieval Heresies from Dialogue on Miracles, V

, Discussion of Waldensians, Albigenses, and "intellectual

heretics" at Paris.

Angelo Clareno, a

Spiritual Franciscan: On Torture  ,

early 14th Cent. ,

early 14th Cent.

Medieval Sourcebook, Primary Documents Jacques

Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers 1318-1325: The Inquisition

Record. [At SJSU] English translation by Nancy P. Stork of selected

confessions by Cathar heretics and Jews to Bishop Jacques

Fournier and the Inquisition at Pamiers.

- B�atrice

de Planissolles (noblewoman, Chatelaine de Montaillou,

later husband of Barthélemy

Amilhac, suspected of Cathar beliefs)

- Barthélemy

Amilhac (priest and husband of Béatrice

de Planissolles suspected of Cathar beliefs)

- Grazide

Lizier (widow of Pierre Lizier of Montaillou (and the local

priest's concubine) suspected of Cathar beliefs)

- Agnes

Francou (member of the sect of the Poor of Lyons - A Waldensian

who refused to swear an oath)

- Aude

Fauré, Wife of Guillaume Fauré, of Merviele:

Confession to doubting the doctrine of transubstantiation

- Guillemette

d'Ornolac, Widow of Bernard Benet d'Ornolac: Confession to

doubting the doctrine of the immortal soul.

- Arnaud

Gelis, also called Botheler "The Drunkard" of Mas-Saint-Antonin:

Confession to communicating with the dead

- Baruch

of Germany: Interrogation of a Jew who was forced to convert

to Roman Catholicism, but remained a practising Jew

- Huguette

de Vienne, wife of Jean Marinier or Jean de Vienne: Interrogation

of a Waldensian who refused to recant.

- Jacqueline

d'en Carot: Interrogation of a woman who doubted the doctrine

of the resurrection of the dead.

- Navarre

Bru, widow of Pons Bru of Pamiers: Confession of having talked

to Arnaud

Gelis about her dead husband.

|

|

"The cardinals dallied with their duty

until 18 March 1314, when, on a scaffold in front of Notre

Dame, Jacques de Molay, Templar Grand Master, Geoffroi de

Charney, Master of Normandy, Hugues de Peraud, Visitor of

France, and Godefroi de Gonneville, Master of Aquitaine, were

brought forth from the jail in which for nearly seven years

they had lain, to receive the sentence agreed upon by the

cardinals, in conjunction with the Archbishop of Sens and

some other prelates whom they had called in. Considering the

offences which the culprits had confessed and confirmed, the

penance imposed was in accordance with rule—that of perpetual

imprisonment. The affair was supposed to be concluded when,

to the dismay of the prelates and wonderment of the assembled

crowd, de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney arose. They had been

guilty, they said, not of the crimes imputed to them, but

of basely betraying their Order to save their own lives. It

was pure and holy; the charges were fictitious and the confessions

false. Hastily the cardinals delivered them to the Prevot

of Paris, and retired to deliberate on this unexpected contingency,

but they were saved all trouble. When the news was carried

to Philippe he was furious. A short consultation with his

council only was required. The canons pronounced that a relapsed

heretic was to be burned without a hearing; the facts were

notorious and no formal judgment by the papal commission need

be waited for. That same day, by sunset, a pile was erected

on a small island in the Seine, the Isle Des Juifs, near the

palace garden. There de Molay and de Charney were slowly burned

to death, refusing all offers of pardon for retraction, and

bearing their torment with a composure which won for them

the reputation of martyrs among the people, who reverently

collected their ashes as relics."

(Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition

of the Middle Ages Vol. III, NY: Hamper & Bros, Franklin

Sq. 1888, p. 325)

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Alphonse's draft letter is held in the French

National Archives, in a dossier called "Grands documents

de l'histoire de France; Florilège", No

notice 00000192, Fonds MUS, Cote AE/II/257 (Cote origine J428/1):

described as "Projet de texte rédigé pour

Alphonse de Poitiers, comte de Toulouse, afin d'obtenir du

pape Innocent IV une bulle sur les poursuites contre les hérétiques.

Au verso figure le dessin d'un hérétique livré

aux flammes. Document non daté, en latin."

The bull ceded to the State a portion of

the property confiscated from convicted heretics. The State

was obliged to take on the responsibility for carrying out

the penalty (since the Church insisted that churchmen should

not shed blood). The relevant portion of the bull read: "

|

|

|

|

|

Further Information on Cathars and Cathar Castles

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you want to cite this website in a book

or academic paper, you will need the following information:

Author: James McDonald MA, MSc.

Title: Cathars and Cathar Beliefs in the Languedoc

url: https://www.cathar.info

Date last modified: 8 February 2017

If you want to link to this site please see

How

to link to www.cathar.info

For media enquiries please e-mail james@cathar.info

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|